I was recently interviewed by David McRaney for a fun podcast called You Are Not So Smart, about self-delusion and the nature of belief. He asked me to debunk the ever-popular aliens-built-the-pyramids-theory, which I blogged about here back in 2007. I don’t think I realized until our discussion that some people believe the pyramids couldn’t have been built by humans because they think they were built in isolation in the middle of the desert (completely untrue, despite the strategic angling of photographs taken at Giza- check it out for yourself on Google Streetview!). You can listen to our discussion in the full podcast here. Re-visiting the topic prompted me to write a short update about some of the recent discoveries that further prove the true origins of the pyramids.

Despite what the media might lead you to believe, we actually know quite a lot about the Giza pyramids and their construction, but new discoveries are constantly expanding our understanding. One of the most interesting recent finds has taken place at a site far away from Giza, at Wadi el-Jarf, where archaeologists have been excavating the oldest known port in the world, dating back about 4,500 years to the time of the pyramids.

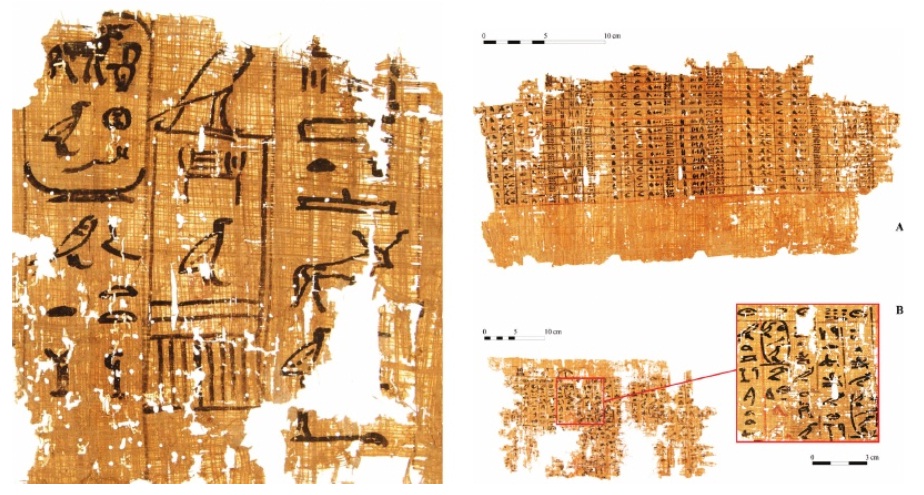

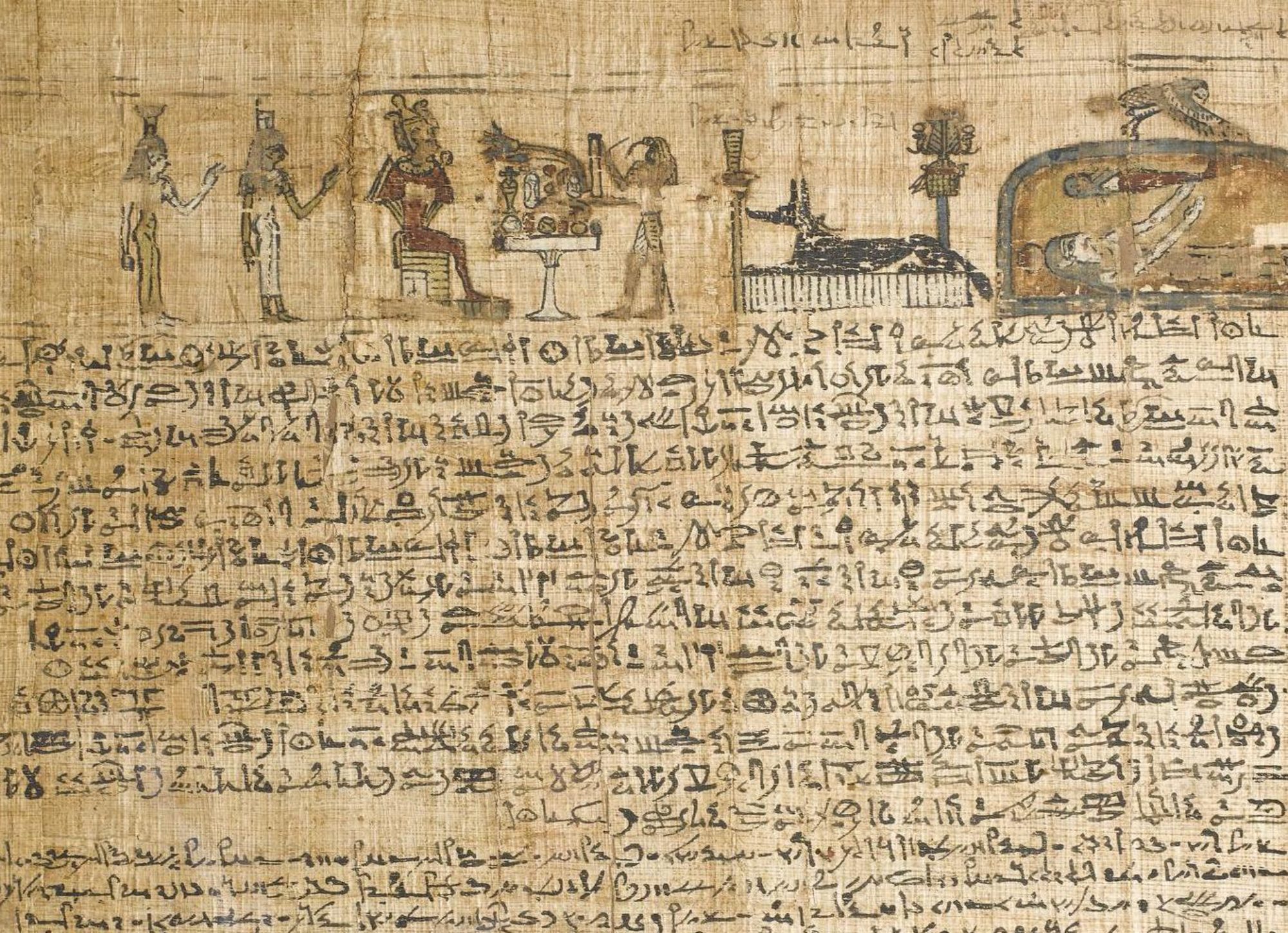

Excavations at the Red Sea site led by Pierre Tallet from the University of Paris-Sorbonne, and Gregory Marouard from the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute, have revealed the remains of dismantled boats used for trade and mining expeditions stored in remarkable galleries, measuring up to 34 metres in length, carved into the rock cliffs. But their most fascinating find so far has been a group of papyrus fragments, which forms the journal of a team who helped built the Great Pyramid at Giza.

This is an astounding discovery: actual documentary evidence of the pyramid building process.

Over a hundred fragments make up a personal log book recording the daily activities of a team led by the inspector Merer, who was in charge of a team of about 200 men. A timetable written up in two columns records the transportation of fine limestone blocks from quarries at the site of Tura to Giza, where they were used for the outer casing of the pyramid. It took four days, using the Nile and connecting canals, to transport the blocks about 10km to the pyramid construction site, which was called the ‘Horizon of Khufu’. The logbook documents these activities for a period of more than three months.

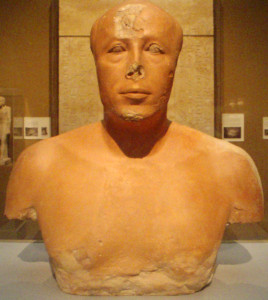

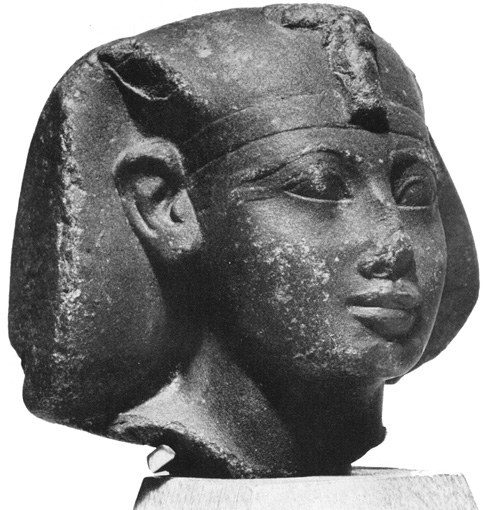

Merer’s journal mentions regularly passing through an important administrative centre, ‘Ro-She Khufu’, en route, one day before his arrival at the Giza construction site. The text specifies that this site was under the authority of Vizier Ankh-haf, half-brother of Khufu. It was previously known that Ankh-haf had served as vizier and overseer of works for King Khafre, Khufu’s successor, and it is thought that he probably oversaw the building of his pyramid and also the Sphinx. Merer’s log book now confirms that Ankh-haf was also involved in some of the final steps of the construction of the Great Pyramid.

The journal was found alongside administrative accounts dated to the reign of King Khufu, the year after the 13th cattle count. Since the cattle count regularly took place every two years, this indicates regnal year 27, the highest attested year for Khufu’s reign. This suggests that the outer casing of the pyramid was being completed at the very end of the Khufu’s reign.

Most people have heard the famous story about how Rameses the Great’s temple at

Most people have heard the famous story about how Rameses the Great’s temple at  was heavily influenced by their more famous neighbours, but yet was an important kingdom in its own right. Tragically, it comes at the cost of losing something we have only just begun to understand.

was heavily influenced by their more famous neighbours, but yet was an important kingdom in its own right. Tragically, it comes at the cost of losing something we have only just begun to understand.