This Thursday, February 18th, the British Museum is holding a free evening of events in connection with their ongoing series with BBC Radio 4, A History of the World in 100 Objects. It sounds like there will be lots of fun events over the course of the evening (18:30-20:30), especially a performance of the Tale of Sinuhe, bringing the dramatic adventures in the poem to life, as well as a talk about the Ramesses II colossus. I myself will be giving a couple of very brief, basic introductory workshops on hieroglyphs. There is also a lecture by Dr. Richard Parkinson at 18:30 on ‘Same-Sex Desire in Ancient Egypt’ and the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep (£5, concessions £3).

The event is listed on the British Museum website, but here is a more detailed schedule of all the activities:

Relax and listen to poetry inspired by Museum objects, recitations of ancient myths, or a talk on mathematics by author Simon Singh. Join a behind-the-scenes tour, view clay tablets in the historical Arched Room, listen to the sounds of Babylon, taste ancient beer, learn to decipher ancient scripts and take the ancient Egyptian civil service test.

All events are free, some are ticketed Tickets are available at the desk in the Great Court, near the entrance to Room 4

PERFORMANCES & STORYTELLING

18.30–18.50 & 19.10–19.30

Babylonian fingers

Ahmed Mukhtar, Baghdad master of the oud (a Middle Eastern forerunner of the lute), gives a solo performance inspired by the Lachish Reliefs.

Room 10a

18.30–19.00 & 19.50–20.20

The world above, the world below

Performance storyteller Sally Pomme Clayton explores the origin of writing and myth making in Mesopotamia. Drawn from the Epic of Gilgamesh, she brings to life a dramatic love story – one of the earliest pieces of literature, written down in cuneiform – which follows a lover’s search for her beloved in the Underworld. Room 56

19.15–19.45

Ozymandias

Patricia Usick, honorary archivist in the Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan, gives a recital of the poem Ozymandias by Shelley, followed by a talk about the statue of Ramesses II in Room 4, and its relationship to the poem.

Room 4

19.30–19.45

Centaur and Lapith

In response to the Parthenon sculpture depicting a Centaur and Lapith, an ensemble of graduates from Central School of Speech and Drama presents a performance exploring the idealised body of Greek sculpture, resistance to cultural absorption, and the ekstasis of sacred processions. Includes students from Trinity Laban and the University of Wyoming. Room 18

19.30–19.40 & 19.50–20.00

The Sphinx of Taharqo

Poet, novelist and Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature Carol Rummens reads contemporary verse she has written in response to the Sphinx of Taharqo. Room 65

19.45–20.30

The Tale of Sinuhe

The Tale of Sinuhe from c. 1850 BC is considered the supreme masterpiece of ancient Egyptian poetry. It will be performed by Gary Pillai and Shobu Kapoor, following their acclaimed recital of the poem at the Ledbury Poetry Festival. Introduced by the poem’s translator Richard Parkinson, curator in the Museum’s Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan. Room 4

WORKSHOPS & DEMONSTRATIONS

TALKS

18.40–19.00 & 19.10–19.30

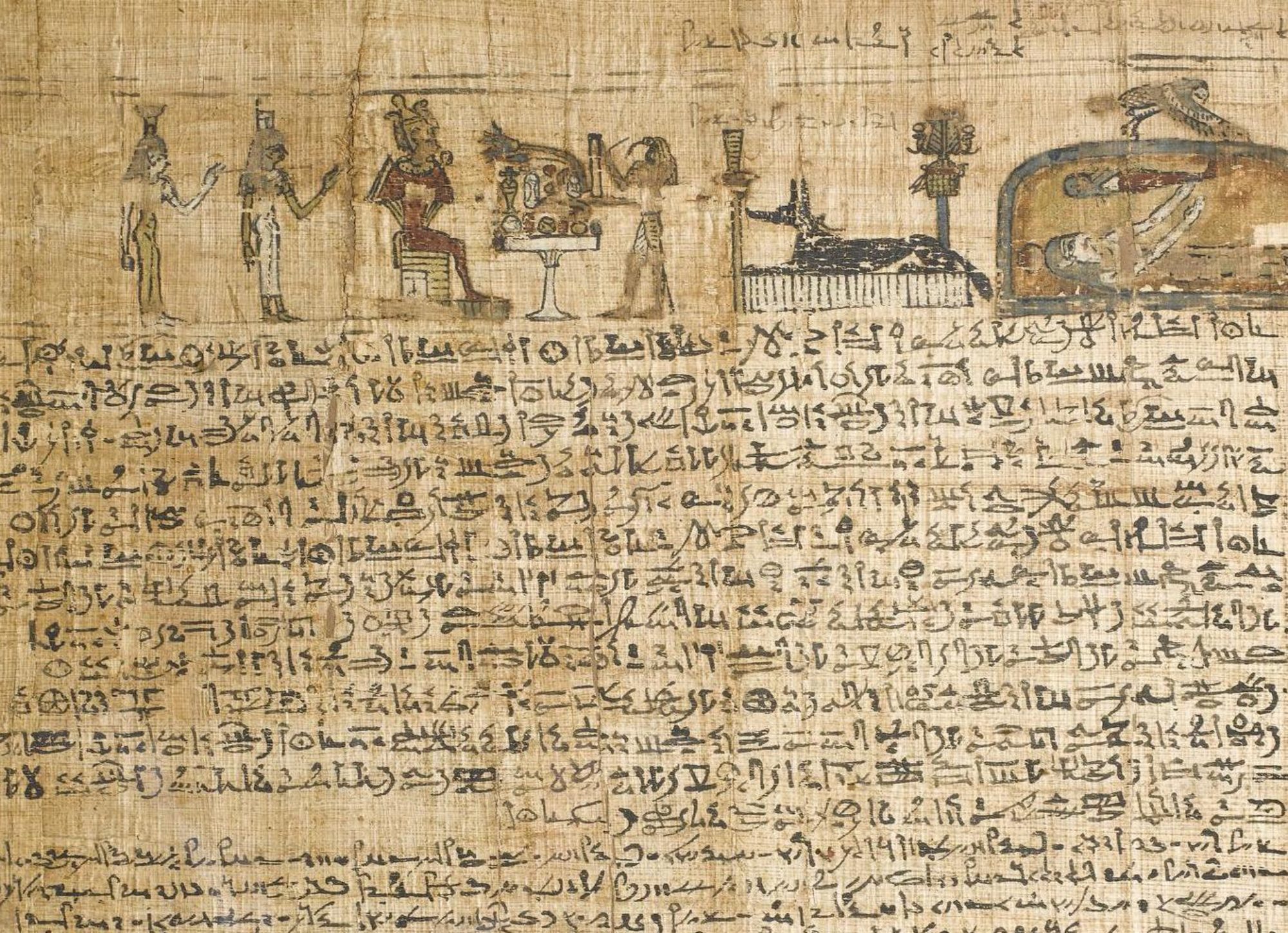

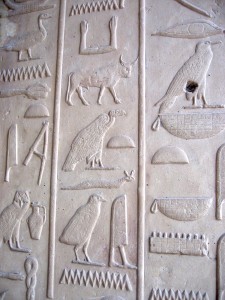

Hieroglyph workshop

A short introduction to hieroglyphs and the basics of ancient Egyptian writing with independent lecturer Margaret Maitland. Learn how to read symbols on the monuments of Ramesses the Great, hear how the ancient Egyptian language sounded, and learn how to write your name in hieroglyphs. Room 4

18.45–19.45

Ancient Egyptian civil service test

Test your wits against the ancient Egyptians and see if you can answer some practical questions based on the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus. With independent lecturer Patrick Mulligan. Room 61

18.40, 19.20 & 20.00

Special behind-the-scenes visit and cuneiform demonstration See ancient cuneiform tablets and a demonstration on cuneiform writing in the historic Arched Room with curator Jonathan Taylor, Middle East.

Meet at the West stairs (north end of Room 4) five minutes before each session. Each session is 25 minutes. Limited places, tickets available at the desk in the Great Court near Room 4

19.00–19.45

The story of ancient beer

Beer has been brewed since the 6th millennium BC and records indicate that beer was first brewed in Mesopotamia. The Beer Academy have picked four beers which take you through different eras of brewing techniques. This tasting and information session will tell you all about the changes through history in how the perfect pint was made.

Great Court

Limited places, tickets available at the desk in the Great Court near Room 4

18.50–19.15

The myth of kingship in ancient Assyria

The throne room relief from the 9th- century BC palace of Ashurnasirpal at Nimrud encapsulates the mythology surrounding the king in ancient Assyria. Independent lecturer Lorna Oakes relates how it also acted as a warning to anyone contemplating usurping the throne. Room 7

19.05–19.40

Mathematical goddesses in Sumerian culture The world’s oldest poetry was made in ancient Sumer in southern Iraq, 4,000 years ago. The mathematics, writing and justice depicted in this pottery portray a vibrant world of gods and goddess, kings and commoners. In this talk, Eleanor Robson, Reader in Ancient Middle Eastern Science at the University of Cambridge, explores how ideals of mathematics, writing and justice were transmitted from the divine realm to the human – not by gods, but by goddesses. Room 56

19.45–20.30

Code breaking

Author, journalist and TV producer Simon Singh speaks on Greek mathematics, the Arithmetica by Diphantus, Fermat’s Last Theorem, ancient codes and code breaking, which he demonstrates with the help of the Enigma Cipher.

Room 17

Programme subject to change. Photography and filming is allowed.

The event is listed on the British Museum website, but here is a more detailed schedule of all the activities:

Relax and listen to poetry inspired by Museum objects, recitations of ancient myths, or a talk on mathematics by author Simon Singh. Join a behind-the-scenes tour, view clay tablets in the historical Arched Room, listen to the sounds of Babylon, taste ancient beer, learn to decipher ancient scripts and take the ancient Egyptian civil service test. All events are free, some are ticketed Tickets are available at the desk in the Great Court, near the entrance to Room 4

PERFORMANCES & STORYTELLING

18.30–18.50 & 19.10–19.30

Babylonian fingers

Ahmed Mukhtar, Baghdad master of the oud (a Middle Eastern forerunner of the lute), gives a solo performance inspired by the Lachish Reliefs. Room 10a

18.30–19.00 & 19.50–20.20

The world above, the world below

Performance storyteller Sally Pomme Clayton explores the origin of writing and myth making in Mesopotamia. Drawn from the Epic of Gilgamesh, she brings to life a dramatic love story – one of the earliest pieces of literature, written down in cuneiform – which follows a lover’s search for her beloved in the Underworld. Room 56

19.15–19.45

Ozymandias

Patricia Usick, honorary archivist in the Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan, gives a recital of the poem Ozymandias by Shelley, followed by a talk about the statue of Ramesses II in Room 4, and its relationship to the poem. Room 4

19.30–19.45

Centaur and Lapith

In response to the Parthenon sculpture depicting a Centaur and Lapith, an ensemble of graduates from Central School of Speech and Drama presents a performance exploring the idealised body of Greek sculpture, resistance to cultural absorption, and the ekstasis of sacred processions. Includes students from Trinity Laban and the University of Wyoming. Room 18

19.30–19.40 & 19.50–20.00

The Sphinx of Taharqo

Poet, novelist and Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature Carol Rummens reads contemporary verse she has written in response to the Sphinx of Taharqo. Room 65

19.45–20.30

The Tale of Sinuhe

The Tale of Sinuhe from c. 1850 BC is considered the supreme masterpiece of ancient Egyptian poetry. It will be performed by Gary Pillai and Shobu Kapoor, following their acclaimed recital of the poem at the Ledbury Poetry Festival. Introduced by the poem’s translator Richard Parkinson, curator in the Museum’s Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan. Room 4

WORKSHOPS & DEMONSTRATIONS

TALKS

18.40–19.00 & 19.10–19.30

Hieroglyph workshop

A short introduction to hieroglyphs and the basics of ancient Egyptian writing with independent lecturer Margaret Maitland. Learn how to read symbols on the monuments of Ramesses the Great, hear how the ancient Egyptian language sounded, and learn how to write your name in hieroglyphs. Room 4

18.45–19.45

Ancient Egyptian civil service test

Test your wits against the ancient Egyptians and see if you can answer some practical questions based on the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus. With independent lecturer Patrick Mulligan. Room 61

18.40, 19.20 & 20.00

Special behind-the-scenes visit and cuneiform demonstration See ancient cuneiform tablets and a demonstration on cuneiform writing in the historic Arched Room with curator Jonathan Taylor, Middle East.

Meet at the West stairs (north end of Room 4) five minutes before each session. Each session is 25 minutes. Limited places, tickets available at the desk in the Great Court near Room 4

19.00–19.45

The story of ancient beer

Beer has been brewed since the 6th millennium BC and records indicate that beer was first brewed in Mesopotamia. The Beer Academy have picked four beers which take you through different eras of brewing techniques. This tasting and information session will tell you all about the changes through history in how the perfect pint was made. Great Court

Limited places, tickets available at the desk in the Great Court near Room 4

18.50–19.15

The myth of kingship in ancient Assyria

The throne room relief from the 9th- century BC palace of Ashurnasirpal at Nimrud encapsulates the mythology surrounding the king in ancient Assyria. Independent lecturer Lorna Oakes relates how it also acted as a warning to anyone contemplating usurping the throne. Room 7

19.05–19.40

Mathematical goddesses in Sumerian culture The world’s oldest poetry was made in ancient Sumer in southern Iraq, 4,000 years ago. The mathematics, writing and justice depicted in this pottery portray a vibrant world of gods and goddess, kings and commoners. In this talk, Eleanor Robson, Reader in Ancient Middle Eastern Science at the University of Cambridge, explores how ideals of mathematics, writing and justice were transmitted from the divine realm to the human – not by gods, but by goddesses. Room 56

19.45–20.30

Code breaking

Author, journalist and TV producer Simon Singh speaks on Greek mathematics, the Arithmetica by Diphantus, Fermat’s Last Theorem, ancient codes and code breaking, which he demonstrates with the help of the Enigma Cipher. Room 17

Programme subject to change. Photography and filming is allowed.

In over three thousand years of history, ancient Egypt was ruled by hundreds of kings; to the untrained eye, they may often seem undistinguishable in their idealised representations, but their stories are more varied and extraordinary than might be imagined. In

In over three thousand years of history, ancient Egypt was ruled by hundreds of kings; to the untrained eye, they may often seem undistinguishable in their idealised representations, but their stories are more varied and extraordinary than might be imagined. In

It has always pained me a great deal that so many people all over the world are genuinely fascinated by ancient Egypt and yet they are so woefully misinformed by sensationalist media, so-called documentaries based in pseudoscience, and the fantasy world of Hollywood. No other ancient civilization is so universally recognized and yet so thoroughly misunderstood. Sadly, Egyptologists are often so frustrated by this that they want nothing to do with the situation; it’s not just a matter of educating people, it’s completely reeducating them, trying to reverse the damage caused by ‘The Mummy’ and even the Discovery Channel.

It has always pained me a great deal that so many people all over the world are genuinely fascinated by ancient Egypt and yet they are so woefully misinformed by sensationalist media, so-called documentaries based in pseudoscience, and the fantasy world of Hollywood. No other ancient civilization is so universally recognized and yet so thoroughly misunderstood. Sadly, Egyptologists are often so frustrated by this that they want nothing to do with the situation; it’s not just a matter of educating people, it’s completely reeducating them, trying to reverse the damage caused by ‘The Mummy’ and even the Discovery Channel.