Recent research into an ‘impossible’ statue at National Museums Scotland led me to discover a previously unrecognised statue-type from Deir el-Medina, the village of Egypt’s royal tomb-builders. These unique statues reinforced the community’s special relationship with the king. They offer insights into the role that statues play in reinforcing power structures.

The settlement of Deir el-Medina is located in the desert near the Valley of the Kings, so the craftspeople could be close to the royal tombs that they were building. Its isolation meant it remained well-preserved and it has become a vital source of information about ancient Egypt.

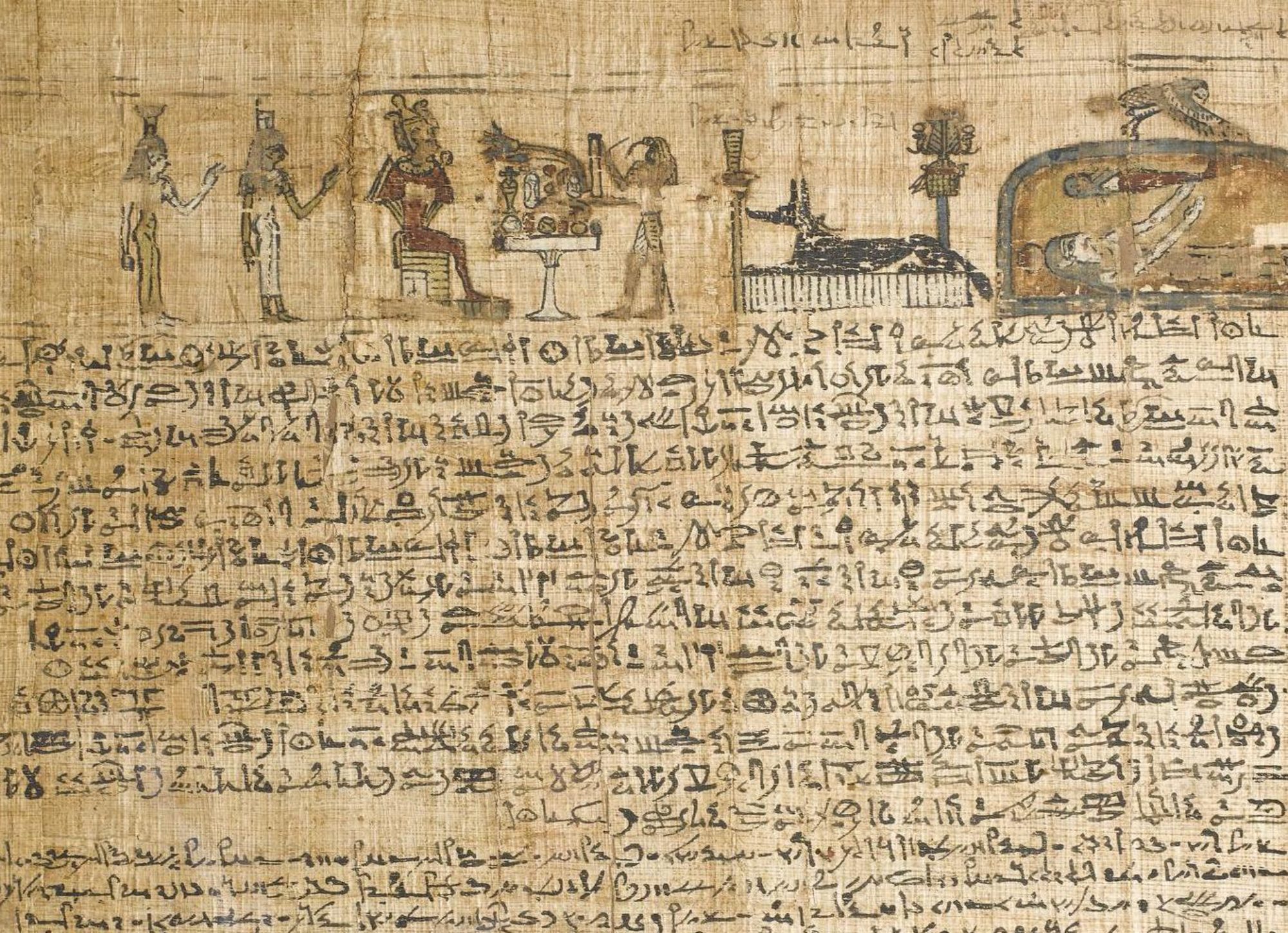

The statue at National Museums Scotland initially puzzled me since its existence seemed entirely impossible according to the rules of ancient Egyptian decorum. According to Egyptological understanding of Egyptian statuary, “a private person is never sculpted together with the king” (Freed 1997) … but this statue shows the impossible: a wealthy state official kneeling to present a statue of a king. How could this statue even exist?

A vital clue came from the archives of Scottish archaeologist Alexander Henry Rhind, which described described a statue that could only be this one as ‘Found in course of excavations near Der el Medinet’.

This clue sent me to review all of the statuary that had been excavated at Deir el-Medina by the French expedition of Bernard Bruyère, which led to two other complete statues of officials dedicating royal statues, as well as fragmentary remains of several other statues! The statues depict viziers (aka prime ministers) presenting statues of a deified form of the reigning king, Merneptah and Ramses III respectively.

They were found in a chapel at Deir el-Medina built to honour the deified Ramses II, who strengthened his power by presenting himself as a god. There is also a statue fragment at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that shows a statue of Ramses Il with the hand of the dedicant. It’s unprovenanced, but an epithet in the inscription connects it to Deir el-Medina.

So clearly a unique phenomenon occurred at Deir el-Medina: high officials broke with tradition to show themselves dedicating statues of the king. This began with a chapel dedicated to deified King Ramses II by the Vizier and his right-hand man, the Chief Scribe of Deir el-Medina, Ramose.

So who is depicted in the statue at National Museums Scotland? No inscription survives, but the floral wreath offers a clue: this rare feature appears only on male statues around the reign of Ramses Il. This suggests the king may be Ramses II himself, who is often shown wearing the blue crown, as in this statue. If so, the most likely candidate for the dedicant would be Chief Scribe Ramose, who helped set up the chapel to the deified king, along with numerous statues of himself, some similar in style to this one.

These unique statues were introduced because it was mutually beneficial for the king to allow Deir el-Medina high officials to have this status-enhancing privilege. It celebrated their close royal connection, reinforcing the officials’ loyalty and the king’s supreme power. Royal burial was an important part of Egypt’s political system and royal succession; the tomb builders at Deir el-Medina were among the few who knew the secrets of the pharaohs’ tombs, and it was worth investing in their support. These statues are 3D representations of a system of patronage – the dynamic of mutual support between the king and those he favoured – which underpinned political power in ancient Egypt.

Statues don’t just passively reflect power structures, they play an active role in reinforcing them.

This research has just been published in the open access proceedings of the Museo Egizio’s conference on Deir el-Medina: check it out, it’s available open access online for free along with lots of other fascinating contributions.