A recent BBC Radio 4 programme “Ghost Music”, which I was involved with, resurrected an old recording of even older musical instruments- the 1939 broadcast of trumpets over 3,300 years old, discovered in the tomb of the ancient Egyptian king, Tutankhamun. These instruments are the only two surviving trumpets from ancient Egypt.

The haunting sounds which were produced in the recording have been almost overshadowed by both the infamous story of accidental shattering of the silver trumpet, and the recent theft of the copper or bronze trumpet from the Egyptian Museum and its miraculous recovery.

The shattering of the silver trumpet destroyed hopes of fully understanding its construction, and it was a shock when the one intact trumpet surviving, which could still offer further information to its making, was stolen. Nor had there been the opportunity to undertake scientific analysis of the trumpet’s material; we still do not know its metallic composition and whether it is made of copper or bronze. Thankfully it was found and hopefully will be studied further in the future.

The shattering of the silver trumpet destroyed hopes of fully understanding its construction, and it was a shock when the one intact trumpet surviving, which could still offer further information to its making, was stolen. Nor had there been the opportunity to undertake scientific analysis of the trumpet’s material; we still do not know its metallic composition and whether it is made of copper or bronze. Thankfully it was found and hopefully will be studied further in the future.

The story of the playing of the trumpet and the disastrous accident that befell the silver trumpet is told in this video:

Various stories have been told about the accident, but it has been said that it occurred when the bandsman, Tappern, attempted to force his modern mouthpiece into the ancient instrument. The use of this modern mouthpiece presumably detracted from the accuracy of the sound produced in the recording, significantly altering their sound from the original. Modern mouthpieces include a semi-spherical cup, which maximizes resonance and enables the playing of a greater range of notes, while the trumpets were originally fitted with just very simple metal rings, purely to make their playing more comfortable rather than produce any effect on the sound.

The trumpets were actually first played several years before the famous BBC recording, by a Professor Kirby, head of the Music department at Johannesburg, when he visited the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Kirby was able to produce three notes but said he doubted whether the highest note was ever used as it required considerable effort, while the bottom note was poor in quality. It is possible that only the middle note was ever used. The trumpet was a military instrument, presumably used not only to rally troops but also communicate. Playing rhythmic patterns on a single note could have served as a military signal. These signals could have been further diversified by using two trumpets of different pitches, which could be why Tutankhamun was equipped with two different trumpets. Trumpeters were referred to using titles such as ‘trumpet speaker’ and ‘caller on the trumpet’.

Kirby suggested that the recording mislead listeners and music critics: ‘What was infinitely worse was that for the broadcast the military trumpeter, finding as I had done that he could get only one good note out of each instrument, fitted his own modern trumpet mouth-piece into each of the ancient instruments in turn, thus completely altering their nature, and enabling him to blow brilliant fanfares quite alien to the sounds head by the Egyptian soldiery of antiquity, and thus misleading listeners-in, including one of the leading London music critics’.

The trumpets were initially discovered in 1922 in the tomb in the Valley of the Kings by Howard Carter. The initial records by Carter made can be read online thanks to the Griffith Institute Archive.

Tutankhamun’s silver trumpet was found in the burial chamber, lying under a calcite lamp wrapped in reeds. The copper or bronze trumpet was found in the antechamber, inside a hinged wooden box in front of the lion couch, which was stuffed full of bows, arrows, walking sticks, as well as the king’s undergarments (!). Confusion prompted by the presence of the military equipment meant that the bronze trumpet was initially identified as a mace.

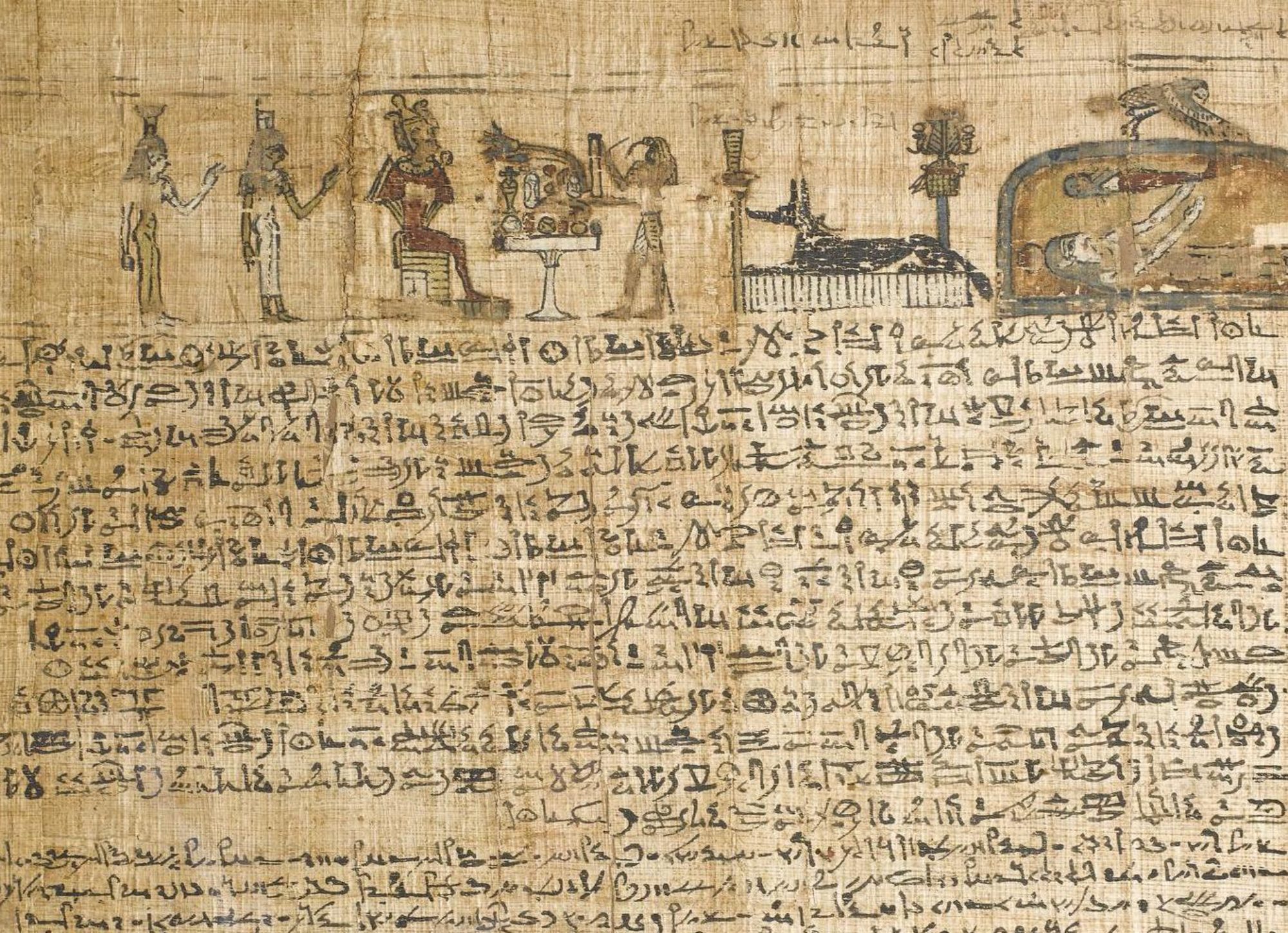

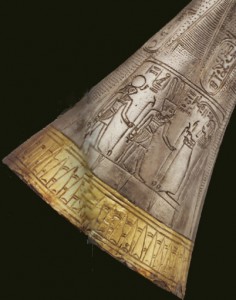

Tutankhamun’s trumpets are both decorated with a square panel on the bell depicting the royal names in cartouches, and the gods Amun, Re-Harakhti, and Ptah. On the bronze trumpet, these deities are joined by the king. These three gods were among the chief deities in Egypt, but it may also be significant that they were also the figureheads of key army divisions, highlighting the instruments’ military role. Nevertheless, their funerary significance is also apparent. The silver trumpet was originally decorated with a lotus flower design, although this was partly erased to make way for the panel. So were the wooden stoppers for both trumpets. The lotus was a frequent funerary motif, a powerful symbol of rebirth, and as such may have been intended to aid the king’s resurrection.

Howard Carter wrote of finding the silver trumpet in his publication of the tomb: ‘Beneath this unique lamp, wrapped in reeds, was a silver trumpet, which, though tarnished with age, were it blown would still fill the Valley with a resounding blast. Neatly engraved upon it is a whorl of calices and sepals, the prenomen and nomen of Tutankhamun, and representations of the gods Re, Amen, and Ptah. It is not unlikely that these gods may have had some connexion with the division of the field army into three corps or units, each legion under the special patronage of one of these deities’ army divisions such as we well know existed in the reign of Rameses the Great’.

Tutankhamun’s two trumpets are the only ones that have survived from ancient Egypt. Previously, there was also thought to be a trumpet in the Louvre Museum. It too was ‘played’ by a scholar investigating ancient Egyptian trumpets and subjected to various tests, such as an oscilloscope, however it was later revealed to actually be a the lower part of a stand or incense burner! Other instruments are well-known from Egypt though, including harps, single and double flutes and other reed instruments, lutes, lyres, sistra (rattles), and clappers.

The drum was the other key military instrument. A wonderfully engaging late 17th Dynasty text tells of a man named Emhab, who practiced his drumming skills until he was invited to audition against another contestant for a position with the army, beating his rival by drumming seven thousand ‘lengths’ (a ‘length’ is presumably a technical term, possibly referring to a rhythmical phrase). Emhab joined the army and drummed on many royal military campaigns, until he was rewarded by the king himself.

The royal trumpeter who played the king’s trumpets, in either a ceremonial or military context, is unknown to us today. Although the 1939 BBC recording of the trumpets may have been technically inaccurate, it offers a chance to connect with ancient experience, sound, and emotion that has captivated many people. In the past, I’ve written about experimental and experiential archaeology and how much we can learn from ancient practices and experiences, such as playing Egyptian board games, making flint tools, or listening to ancient poetry. The BBC recording may be the only chance we will ever have to hear the sound of ancient Egypt trumpets; the possibility of further damage in sounding the originals is too great, but it may be possible to make accurate replicas one day. However, even if we can never truly replicate the trumpets’ sound again, the Egyptians left us an almost equally moving impression of their wondrous sound. In the tomb of the fan-bearer Ahmose at Amarna, there is a unique representation of a marching army. The scene depicts the figures in the normal ancient Egyptian arrangement of registers (one might say similar to the strips in a comic book), but its key feature is the unusually evocative element of an empty register, stretching out before the lone figure of a trumpeter. Surrounded above and below by marching troops of soldiers, he holds his trumpet to his lips while the empty space before him suggests the loud, clear notes of the blast echoing forth. It is a beautifully poetic use of empty space, symbolizing the powerful but unseen effect of the trumpet’s sound, still resonating across the millennia.

I just love experimental archeology, but I feel like not enough of it is being currently done.

Has it been totally replaced by advanced technology testing? I sure hope not.

Lovely and fascinating post.

Thanks for this post. Very nice companion to the BBC program. I often wonder whether Carter played those trumpets upon discovering them…would you by any chance know if he wrote about doing that? Thanks.

Dear Sir / Madam

I am truly moved to see the photos of this trumpet, we call suranai in Hunza / Nager valley in norther Pakistan. It just amazing to known that our musical instruments origin is ancient Egypt. And it is even more amazing when we hear it during celebrations and weddings in Hunza.

Thank you so much for this post.

Respectfully yours

Kanjudi

You can see replicas of both trumpets and their wooden inserts in the EMAP (European Music Archaeology Project) exhibition – currently (rest of 2016) in The abbey, Ystad, Sweden. These will then travel to Spain, Cyprus, Slovenia, Rome and the UK. There’s more on the project at http://www.emaproject.eu. It was a wonderful experience to make these and play them.